Metamorphoses and the opening of portals

I should have known—Ovid's magnum opus is no ordinary work.

I love it when a book fascinates me enough to become a doorway to things beyond the page.

One wonders: shouldn’t this be a regular occurrence? But, no. I can like a book, thank the author for writing it and move on to the next one. Or I can meditate on it and be content with letting it simmer in my psyche. In either case, the gate to other intriguing things in the physical world remains unopened.

But with some books, my curiosity awakens like a serpent roused from its slumber. I want to know the originator of the work and read or listen to more words by them. I want to follow up on the references made. I want more tales in the same setting or with similar characters. Most of all, I want to know how the book lives beyond what is printed between its covers.

Reading Metamorphoses in the summer was an experience like this—one that opened multiple doors I’m just beginning to explore.

Lanua numerus unus: Auctor

(Door number one: The author)

Written in 8 CE, Metamorphoses is a Latin narrative poem that is regarded as one of the most influential works in Western culture. The poem traces the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar in 15 ‘books’ and remains one of the most referenced sources for mythological narratives.

Without a singular hero or figure to follow, chaos, passion and change reign in the 250-something myths we read. When I looked closer, though, I could discern that it was Ovid and his interpretation of Greco-Roman mythology that we were following.

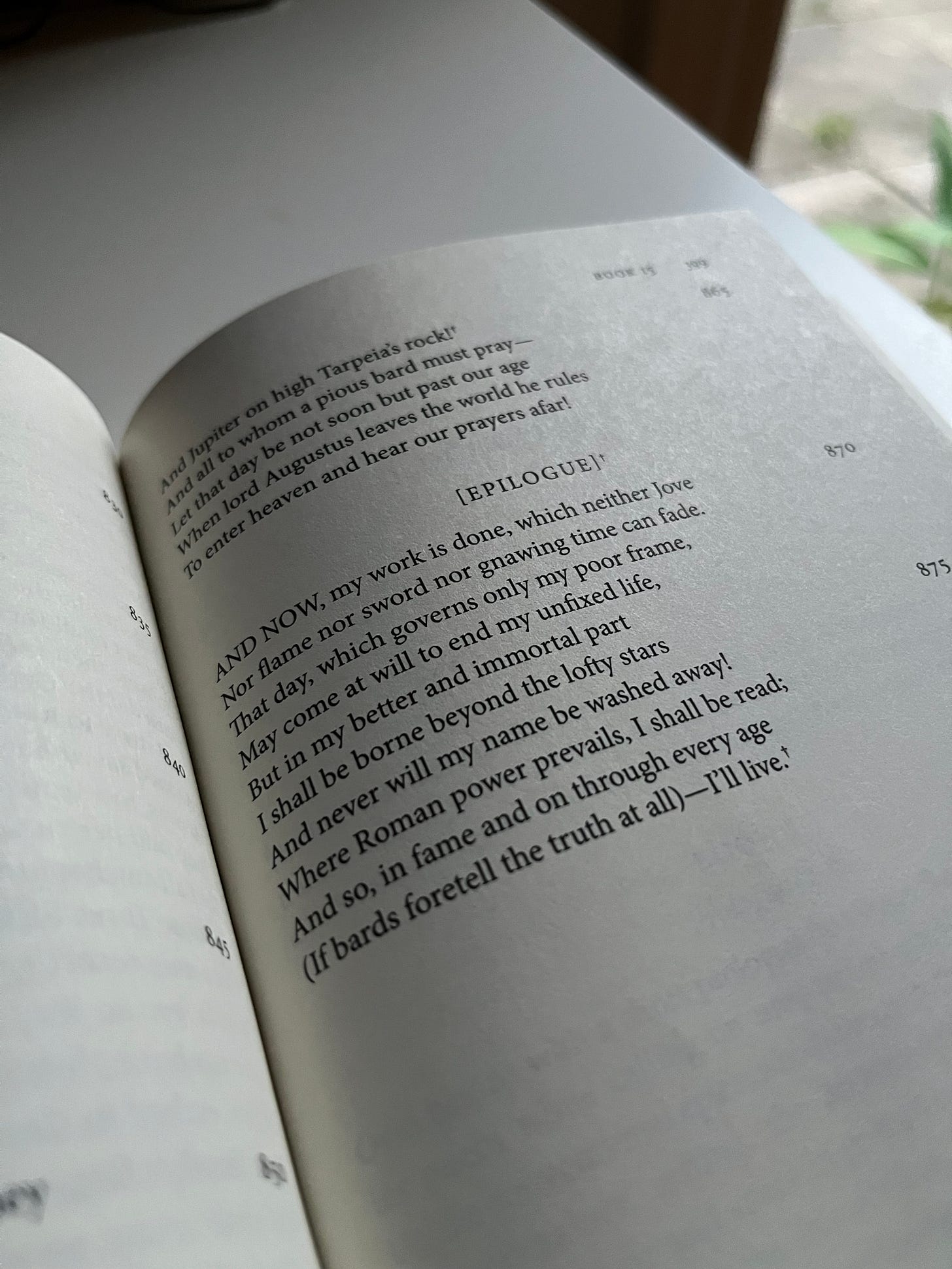

As it turns out, the point of Metamorphoses is not to glorify or worship a mythological hero, god or even the Emperor of Rome. The aim of the work is the work and, by extension, Ovid himself. The end of the poem makes the case for this:

Ovid could have ended with moral platitudes, a prophecy about the state of the world or how Gods and humans will continue to wreak havoc, so ‘this is how we should conduct ourselves.’ Instead, he chose to end with words about himself and his work. It seems Ovid had a healthy sense of ego and wasn’t afraid to own it in public or print.

The importance that the poet accorded to himself and the poem made me curious about his other work. When I went to look up what else I could read from him, I was pleasantly surprised: Ars Amatoria (Guide for Lovers) taught the nuances of seduction in a tongue-in-cheek manner. Remedia Amores (Cures for Love) advised how to unspool yourself from an unhappy love affair. Medicamina Facei Feminae (Women’s Facial Cosmetics) defended the use of cosmetics by Roman women and went the extra mile by suggesting five facial treatment recipes.

These works were followed by a tragic (and now lost) drama about the mythical sorceress Medea and Heroides, which is a collection of 21 letters penned from the perspective of female characters in Greek mythology to their absent male lovers. Fasti and Metamorphoses came after these.

Publius Ovidius Naso, thus, has been gleefully inducted into my TBR list.

Lanua numero duos: Art

(Door number two: Art)

Metamorphoses is perhaps the most widely illustrated text in European literary history apart from the Bible. This meant that after going through the poem, I could look at quite a few artworks and say, “Yes! I recognize the story behind that painting.”

Some pieces were, of course, more captivating than others:

Now, there are more museums on my bucket list than previously. I'm very interested in repeat visits to the Art Gallery of Ontario, in reading books like …isms: Understanding Art and in stopping to appreciate the work that goes into a painting I encounter online and offline. I might even take another stab at learning as many constellation names and locations as possible since I have at least one version of the story behind them.

Ostium aeternum: ipsa

(Eternal door: She)

It took me about a month to read Metamorphoses. After finishing the book and going down the aforementioned paths it opened up, my reading experience reminded me of this beloved quote:

“People forget that books are the original internet. Every footnote, every citation, every reference is essentially a hyperlink to another idea.”

- Maria Popova from a 2019 interview

I read to discover, be enlightened and find new ideas and ways of being I can make my own.

Deeper than that, though, I read to be transformed, to actively shape myself, my attitudes and thus, my trajectory—to undergo my very own metamorphoses, one idea and one door at a time.

"Most of all, I want to know how the book lives beyond what is printed between its covers." Banger line. Thank you for articulating how I feel about a lot of the stories I've read.

The fact that this came from multiple drafts makes it even sweeter. There were so many things about this blog that caught my attention but most of all it was knowing the intentionality that’s gone behind it. Every sentence is crisp. Love the images too! 😍🩷

Waiting to read the next one. 🥰